is it still the action of choice? |

Is the future all-mechanical? Organs and organ-building in Britain today (No.2 of 6 articles published in Choir & Organ in 1997 under the heading 'Raising the Tone') |

In the English-speaking world, the revival of mechanical action has stimulated a long-running and frequently silly debate, in which theoretical arguments about reliability, design discipline, authentic performance and precision of touch have been used without much account being taken of the real world: a real world in which some fine organs are too big to have mechanical action, in which some fine music is too difficult to be played on mechanical action, in which some builders of tracker organs are less than perfect, and in which the majority of organists are less than brilliant at manipulating the chiff of un-nicked pipes by digital skill alone. I hesitate even to attempt to deal with the subject, but it has to be done.

It is the organ builders who are largely responsible for the success or failure of the results. I cannot answer for organ builders in general, but as an ex-member of the British organ-building community I can offer myself as an example of what the current trend really means in the drawing office. Why does a modern organ-builder prefer to build his instruments with mechanical action? Is it really the action of the future?

I have always been somewhat distrustful of the musical arguments for mechanical action. For example, much has been made of the possibility of controlling attack through touch: E. Power Biggs was the first person I heard preaching the idea that a good player could actually [ital] modify [ital] the chiff of un-nicked pipes. However, visits to unaltered old organs in many nations have convinced me that first, many really didn't chiff that much, and secondly that few had responsive enough actions for such subtle nuances to make anything more than a minor contribution to the overall effect. In any event, on an organ voiced in the old 'naturally irregular' manner no two adjacent pipes chiff the same way at the best of times.

I have also observed that musicians are, by their nature, bad at explaining what exactly it is they 'feel' under their fingers. Having listened to people talking about 'pluck', 'response', 'holding weight', and 'repetition' it has become clear that no two performers define these terms in quite the same way. Organists are themselves part of a heap of intangible variables, and their descriptions of what happens when they play are deeply subjective.

However, the question of 'articulation', the deliberate shortening and lengthening of note values in order to give expression in an otherwise dangerously inexpressive instrument is, I think, of fundamental importance, and may be one of the keys to the organ-builder's enthusiasm (and that of many players). The real problem with even the very best, fastest and most reliable electro-pneumatic action lies in the position of the key contacts. No equivalent of 'tracker touch' can ever exist on a keyboard with electric contacts, because the contacts cannot be set to fire at the point when the key starts to move. To avoid over-sensitivity and endless notes sounded by brushed fingers the contacts are set to fire after two or three millimetres of movement. Now it is obvious that precise timing of the start and end of the note is impaired, and that this problem could only ever be partially alleviated by an artificial tracker touch. Of course articulation can be controlled to an extent on an electric action keyboard, but I submit that it is more difficult to do, except in reference to the moment when the finger presses the keys (harpsichord touch) or the key hits the key bed (piano touch). In other the position of the contact is arbitrary (although it may have the curious benefit of improving repetition).

Now, unlike the skill of controlling chiff, articulation is a game anyone can play. It does not depend much on dexterity or on the quality of the organ. Even as an amateur player I can bring life to any musical phrase, however simple, by expressing it through variations in note value - and this is of as much value in Vierne's Berceuse as it is in a Tierce en Taille. Moreover, as a listener I find it quite easy to hear the articulation in an otherwise quite average performance, provided the action is mechanical. Barker lever or charge pneumatic actions preserve some of the detail. On exhaust pneumatic, electro-pneumatic and direct electric much of it is lost.

Small tracker organs - one or two manuals - are demonstrably reliable (300 years really is possible for such instruments), obviously perfectly comfortable to play (the 'great engineering advances' of modern action design have been significant), and thanks to the revival in casework many of them look pretty splendid too (How good they actually sound is a matter best left to another article). But as soon as you get to three manuals and larger, the trouble begins. A modern three manual mechanical coupling chassis renders an organ less reliable than its 18th century counterpart (with only a shove-coupler or two at most). Individual departments get large enough to increase the weight of touch, and risk robbing in the bars. In fact any slider soundboard with a manual 16' stop begins to challenge the viability of tracker action if it then has to be coupled in regular use.

What actually happens is that the organ builders all avoid the issue furiously: they either build true historic copies (where the problem doesn't arise - 'yes, we really are going to make the action as heavy as in Bach's day') or they cheat. Those who build eclectic mechanical action organs all include pneumatic or electric devices to make life easier. A Van den Heuvel may have Barker machines as in a Cavaill»-Coll; a big Rieger has pneumatic assists or balanciers under the pallets; a big Klais has electric coupling. All these methods bring problems with them. A Barker machine is expensive, space-consuming and noisy. Balanciers are touchy and the repetition can suffer. Though electric coupling is cheap and reasonably reliable it is impossible to synchronise the two actions.

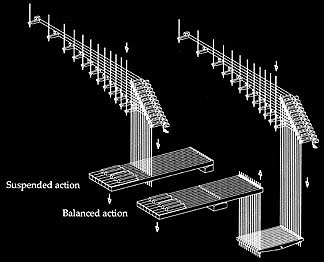

In all three recipes, some virtues of a simple mechanical system survive, enough at least to give encouragement to organ builders in their struggle for perfection. Each builder will express his or her preference. My own current position - obviously related to the two big organs built by N. P. Mander Ltd. while I was employed there as a designer (St. Ignatius Loyola, New York, and St. John's College Cambridge) - is to use suspended key action where possible, with mechanical coupling, some balanciers (bottom 18 notes only), and pneumatic off-note actions for a few individual wind-hungry and slow-speaking basses (thus at New York the Pedal 32' flue is pneumatic but the 32' reed is mechanical).

By stating this preference I challenge the ideas set out by Paul Hale in his article in The Organbuilder for July 1996, where he describes the thinking that went into the organs at Southwell Minster and suggests that 'flirting with suspended actions is a blind and unpredictable alley which should be abandoned for large organs as soon as possible'.

I hardly dare enter into debate on this detail, as my own honest perseverance in this field and two widely appreciated instruments have by implication been dismissed out of hand. Besides, there is no right or wrong answer on this matter, nor on any other of the thousand and one intricacies of action design. It is, genuinely, a matter of opinion.

These are scientific arguments mistakenly applied in an area of what used to be called 'Natural Philosophy'. No one argument can be conclusive, for in the arts of instrument-making and playing there are far too many variables to be pinned down to a formula which generates a yes/no answer. How otherwise could a great organ that breaks all the 'rules' (say the Henry Willis III Liverpool Anglican Cathedral or the E. M. Skinner at Girard College) be quite so downright marvellous in practice? Even the most hardened tracker addict has to be clear that the arch-romantic organ with remote console has a valid and fascinating voice, especially in a great building.

It depends what you are looking for. The methods suggested by Paul Hale are one valid route. Given that the new organ on the screen at Southwell has neither a coupling chassis nor any bellows (schwimmer regulators are used instead) and includes a considerable body of second-hand pipework, we can reasonably assume that one of the first priorities in Paul's design has been to complete the specification of the organ within constraints of budget and space. The presence of three electronic pedal ranks tends to confirm this. Moreover, when one reads Paul Hale's assertion that his ideal organ has four complete manual divisions (beyond which 'little else is needed'), it becomes clear that he is a fan of large organs with lots of stops. In fact the two organs now in Southwell Minster, one of the smallest cathedrals in the country, contain a total of over 5,900 pipes, only about 1400 fewer than in St. Paul's Cathedral.

I have not been to Southwell recently, but I know from the opinions of those who have and from the reputations of the builders concerned that both organs are good instruments. Personally, however I regret that more effort seems to have been put into quantity than into the creation of a musical instrument designed, scaled and made for the building in which it stands. The very few parts of the total scheme that remain mechanical seem only to exist as a token reference in something that is descended from the giant schemes of the all-electric late romantic era.

Now these offhand remarks will probably cause Paul Hale to hurl his copy of Choir and Organ into the waste paper bin, not least because I am not a musician, let alone a professional organist. I present them here, not because I believe that I am right, but simply so that we can all see that such a debate must exist and that it should, ideally, be conducted at a much more serious level- it is a valid representative of all artistic arguments about organ-building, and reminds us that no progress in the craft can be made without the most careful examination of detail and critical study of the results. Is mechanical action still relevant? - of course it is: the fact that it is debated so hotly proves that it is a subject at the sharp end of organ building today. There will be many more such instruments.

Mechanical action is not a 'retrograde' step; it is part of progress. It is not that the pendulum has swung back: Foucault showed that no pendulum ever quite retraces its steps and this holds true in metaphor as in reality. The debate sharpens our ability to assess organ building as an art. How we may further refine that art, beyond the mere question of mechanism, will be tackled in the articles that follow.