(No.2 of 6 articles published in Choir & Organ in 1998-9 under the heading 'Spit and Polish') |

How is such a chorus built up? The recipe is as simple as it could be - all the ranks in the principal chorus are roughly the same scale and power, and a pipe one foot long in the mixture is likely to be very similar to a pipe one foot long in the facade. Upperwork is not softer than foundation work - just set further back in the case. Quints are not smaller or softer than unisons - there are just fewer of them. A couple of further important details complete a picture that was not always correctly observed by neo-classical imitators: first, it is not unusual for the smaller pipes to have rather high-cut mouths, with the tone become increasingly dull as the pipes get shorter; secondly, in early slider soundboards with narrow windways the upperwork is often slightly short of wind when used in combination.

My description is grossly simplified, but elements of this 'straight-line' method are to be found in seventeenth and eighteenth century organs all over the world, whether in the Netherlands, Scandinavia, Germany, Poland, Bohemia, France, Italy or Iberia. It is no exaggeration to say that this simple and straightforward approach to the chorus is the backbone of the organ tradition, and a full understanding of its workings is a vital part of a voicer's education. Though at first sight the recipe appears crude and unsophisticated, the resulting sound is exceptionally complex and satisfying. The interaction of unison and quint ranks of similar scale and power creates a complex aurora of additional sound - difference tones and addition tones - that can be achieved in no other way. The result is equal to more than the sum of the parts and is lastingly fascinating to the listener.

If you recommend this method to an English organ-builder, you are unlikely to get a warm reception. 'The straight-line chorus - like Schulze? Well! We don't want that!'

Everyone knows - well, at least, they know if they have read the copious descriptions in the organ magazines of yesteryear - that Schulze's mixtures come on with a crash as deafening as any tuba, and that any idea of gradual crescendo or 'build-up' in his instruments is quite impossible.

It is a shame that popular opinion is still all too easily guided by the critics of yesteryear - men such as Gilbert Benham and Noel Bonavia Hunt - who, whatever their fascination with the work of Schulze, saw no point whatever in the classical flue chorus. In the 1920s and 30s English builders, musicians and critics were all wedded to a concept in which upperwork was firmly subordinate to the foundation, sometimes even reduced so far as to represent a 'scientific' presence of delicate upper partials. Even George Dixon's oft-repeated claim to have 'restored' the intelligent use of upperwork in this country only bears examination in relation to the mixtureless organs of Hope-Jones; the characteristic Dixon design of circa 1910 will run to a delicate swell mixture only - the great organ 'Harmonics IV' is an overtone-stop (containing tierce and septieme) in which breaks to lower pitches are avoided for as long as possible. It is in fact a kind of cornet, designed to bridge the tonal gulf between diapasons and reeds, and any brilliance it produces is of a highly idiosyncratic kind.

If Dixon had been kinder to his immediate predecessors he would have recognised that in some circles upperwork never died. In 1890 Hill & Son built their magnum opus at Sydney Town Hall, with four large mixtures on the great organ alone (fourteen ranks in all), and in 1897 Lewis presented his own masterly version of the classical concept at Southwark.

Schulze was not alone in espousing the 'straight-line' sound, though there are aspects of his way of doing it that make his instuments unusual. In fact, the mixtures in a Schulze chorus may be smaller than the unisons, but at Armley and Doncaster they are positioned at the very front of the organ. No wonder they come on with a crash! In addition, Schulze espoused brilliant tone in all his flue work (especially where he used wide mouths), and with a characteristically nineteenth-century scientific thoroughness, made sure that every pipe, even the very smallest, received an ample supply of wind. All this contributed to a chorus sound that hovered on the very brink - there was brilliance in plenty, some of it conventional, but some of it so intense and complex as to set one's teeth on edge. The result is wonderful, and deliberately full of tonal tension, but it is not quite the chorus of classical tradition.

Hill and Lewis, on the other hand, worked in a more sober manner.

Lewis maintained an interest in Schulze's brilliant tone, but handled it with English suavity. The mixtures were big, but set back in the organ in the conventional way and are therefore more blending. The rather hard foundation tone was intended to be covered by the use of the flutes - and where the Lewis harmonic flutes are provided the balance becomes distinctly warmer and more sociable.

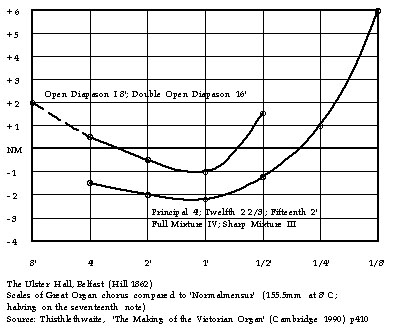

On the other hand Hill's choruses were not brilliant in tone at all. There is no hint of Schulzian brightness, and in this respect the Hill sound belongs to an older tradition. However, the upperwork is handled with bravura. At the Ulster Hall in Belfast the great chorus of the Hill of 1862 survives with relatively little change. Principal, Twelfth, Fifteenth, Full Mixture IV and Sharp Mixture III are all to the same scale and power; the Open Diapason and Double Open Diapason are larger. And what scales! The two-foot rank of the Full Mixture starts at almost two inches (50mm) in diameter, and in gleeful ignorance of any regular halving or Toepfer progression ends with at the top of the keyboard over six notes larger than normalmensur. This is heroic stuff!

Listening to the finest surviving work of Hill or Lewis, the link with the chorus of tradition is immediately apparent, even though the organs are romantic in their overall concept and in their luxurious provision of other tones. The nobility and grandeur of the fluework in such instruments is unforgettable, and the experience of listening to, say, Southwark brings to mind comparisons with the F.C. Schnitger at Alkmaar. How unlikely this seems at first sight, that an organ of 1897 should belong to the same artistic continuum as one of 1725! And yet, was that not exactly the point of Lewis's 'Protest at the Modern Development of Unmusical Tone' also published in 1897?

Why I draw this subject to wider is because I wish to amplify a remark I made in 'The History of the English Organ':

'there are few [British] builders in 1995 who can make a flue chorus as noble and convincing as the best by William Hill or Thomas Lewis'

This is a sad admission to have to make, and yet I am certain that it is true. I am also certain that the lack of a sure-footed ability to produce good flue choruses is an element in the repeated loss of major presitigious contracts to overseas builders. That continental chorus sound, which is present to a greater or lesser degree in almost every one of the imported organs of the last generation, has not always been available from the home team - despite the splendid example set by our Victorian forebears.

My last series of articles explained how British organ-building has at last rediscovered its craft traditions and is embarking on an artistic revival; coupled with this it is necessary to explore anew our assumptions about blend, balance and tone. The succesful production of a traditional principal chorus is at the root of that understanding, and will examined further in the next issue.