Pauloni in Paris

This essay first appeared on the electronic

mailing list

![]() Piporg-l

Piporg-l

Part 2

INTO THE BLACK HOLE

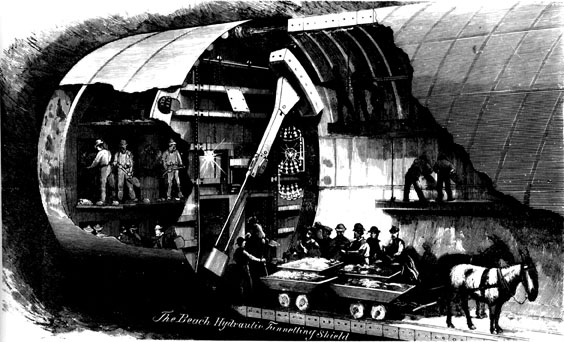

They actually started building the Channel Tunnel over a hundred years ago. Earlier still, in 1824, the Brunels, Father and Son, had started their pioneering push through the stinking brown sludge under the Thames at Blackwall (Father died, the son emerged at the other end somewhat the worse for wear in 1843). Once they had proved it was possible (quite disregarding all questions of cost, delay and large-scale loss of life, all of which were considered to be small prices to pay for so brilliant an advance in engineering), the English Channel was quite simply the obvious next waterway to be conquered in the march of progress. There would be a tunnel under the Channel.

Politicians continued to argue about it for the next one hundred and forty years simply because that was what their predecessors had done. The railways alone had demonstrated conclusively to every man, woman and child in the civilised world that once an idea came to a great engineer, he could transform their entire lives in a flash so brilliant and so commanding that there could be no further obstacle. It was quite demonstrably inevitable that the engineers alone, with their mindless enthusiasm for their own skills, would eventually form a political lobby strong enough to drive the passage under the Goodwin Sands towards Calais. After all, the Romans would have done it - if they hadn't had to leave so early!

The Channel Tunnel

One attempt was made in the nineteenth century, but from the English side only. The French took to the New Iron Age later than the English or indeed the Germans, not from lack of ability (after all Cugnot was driving round Paris in his horribly dangerous steam-lorry in the 1790s), but unfortunately delayed by certain periods of social disorder chez eux. However, once engineering genius had asserted itself in the glorious work of Gustav Eiffel the French decided that this one branch of Science was worthy of elevation to the highest rank, otherwise only occupied by the two Arts: Painting and Haute Cuisine. The great achievements of the French in this area since Eiffel's Tower have been as baffling and as dazzling as a canvas by Ferdinand Léger or stained glass by Marc Chagall. Trains that travel on rubber tyres, cars that look like sardine tins, scyscrapers made of primary-coloured extruded plastic, and a national frenzy for the full-blooded idiocy of Dr. Frankenstein's genius, but applied to every last detail of mechanical life. America may have more gadgets per capita than France by a factor of ten, but I cannot begin to explain just how peculiar the French vision of the future is.

So it was eventually the driven sense of purpose of the French that crumbled the hesitant, neurotic and downright stingy attitude of the English and turned the Chunnel project into a reality.

Un Tunnel sous la Manche?? - but of course.

Knowing a fun party when it sees one, the House of Commons then at last got its act together and redeemed the British National Pride by making the Chunnel into that perilously instable arrangement: a joint Anglo-French venture. And people subscribed money. Some of my Friends even. I did not. Having taken a special interest in the work of the Brunels and examined the whole nature of the subject: 'tunnel' in my mind over a period of years, it was clear to me from the outset that the whole thing would be a disaster. BIG TUNNELS ALWAYS ARE.

So it was a black hole in the white sea wall of Albion that we entered on Sunday morning, a charred orifice. Blackened, as you may know by a recent fire.

The fire just added insult to injury. Over the last twenty years the poor lunatics who decided to make this tunnel their career have lurched from catastrophe to catastrophe: the costs sprialling, the work slowing, the budgets failing, the debts multiplying - and of course several quite good friends of mine went with them and are now creatures of the gutter. To have a fire as well, so soon after opening! - just when public confidence was growing and a real spot of light was at last visible through the impenetrable gloom of the word: 'tunnel'!

But I must say that the company is doing a splendid job in the difficult circumstances. There is this marvellous moment when, wearing little plastic capes dutifully provided by the railway, all 1,420 passengers travelling on the service climb individually down the carriage steps by the light of hurricane lamps and begin to make their way on foot through the debris-strewn and flooded chimney towards the French train 2000 metres away. And then there is the meeting with the party coming the other way, an exchange of gifts, and toasts are drunk.

By the time you board the SNCF express with its Ahlstrom power-plants that run on supplies both DC and AC, from either catenary or third rail, at almost any voltage and frequency you care to mention, you have been made well aware of the true nature of the French folie de technologie. They have spared no expense. They have actually trained all the staff, including the wheel-tappers, to speak English without an accent, EVEN THE ONES FROM BIRMINGHAM.

______________________________

It was at this point that I woke up. I was on the French train. It was flying through the slow unfolding ripples of grey wintery Northern France at one hundred and fifty miles an hour. A disembodied voice hummed across the sterile air:

'Ladies and Gentlemen, we apologise for the slight delay you have experienced in travelling by Eurostar Sous Manche deLuxe Turbo Express, and we will arrive at Paris Gare du Nord in precisely three seconds.'

Then the doors slide open with a snake-like hiss and a large hydraulic lever lifts you out of your seat and puts you and your luggage on a trav-o-lator in the Metro.

And at this point I realised I was in company. I was staring at a fur coat. An enormous fur coat. A fur coat that blocked my view of the sun. A huge friendly hand landed on my shoulder:

'Parigi!!! I LOVE this city!!!'

I was abroad with Count Pauloni.

I let out a shriek and we all fell off the end of the trav-o-lator in a heap.

('We' were: your scribe, Basil Bysshe Bye Bagshawe Bicknell, my man Cedric, nobilissime the Count Paulo Pauloni, and the Count's entourage, viz: -

From the Abbey of the Mauve Thought in the Goldhawk Road Paulo had brought Sister Muriel, his spiritual advisor (Father Paul remained in London to attend to Parish affairs). From Boston came Horatio Cordy-Bassett, the magician who has brought stunning and newly-minted life to the paper-roll organ performances of LeMare, a man who glints with the delight of having produced one of the most delightful time-bending conjuring tricks to have been played on a modern music-loving audience. And then to complete the group, from New York, was Brad Jaeger III. Brad is of course the dedicated curator of the Elhanan Q. Hackenback organ in St. Gladys de La Croix. He was just beginning to recover from the pre-christmas tuning of that heroic instrument and it became noticable during the course of the trip how he regained his usual colour and vitality.)

Cedric was at the bottom of the heap. I was above him. I could recognise Horatio by his socks, and a smell of lavender water indicated that Sister Muriel was nearby. I could see a suitcase label with my left eye, and an umbrella stand with my right. Brad's spectacles were in my left hand. I could only assume that the fur coat was at the top.

We were in the lobby of the Hotel Récamier, a clean, cheap, warm, friendly pension about the width of a stair rod in the south-east corner of the Place St-Sulpice. Staff (clearly chosen for their thinness and agility), fussed round us, the heap was disentangled, our bags were spirited away, and we were led meekly to our rooms to bathe and change.

It was lucky that the hotel was warm, for when we emerged in a group an hour later to examine our surroundings it was to find a vision of uniform frozen grey: Paris withering in a Russian winter at minus four degrees centigrade. I have been in Boston in a vicious cold spell and I know that it there it begins to hurt in one second flat, but though not so cold, the bone-chilling dampness and the hideous low grey skies of Northern Europe in a deep frost are a vision of an alternative and horrid underworld.

Paris withering in a Russian winter

We were silent and could see no sign of life. Was that a small dog struggling in the icy fountain? Did that heap of rags on the church steps move? Why was one streetlight flashing on and off intermittently at Lunchtime? The flickering sodium light illuminated something very odd.

It was mauve. Sister Muriel was impelled towards it as if by instinct. Brad, Horatio and Cedric were drawn by curiosity. Paulo put on his pince-nez.

'It's only a motor-car!' I shouted after them, but it was no use. They were having their first Close Encounter with the French National Mania. Now to me the cars made by Panhard in the 1950s are a miracle of daring. A tiny engine, that in the United States would be considered underpowered for a sewing machine, is blown so hard that they had to machine the cylinder heads out of solid metal - to stop the perpetual blowing of head gaskets. They then put this gizmo-ette into a metal object the size, shape and weight of a kidney-bowl that nevertheless had doors and seats for four people. If you drove with your foot on the floor for half an hour the speed would eventually climb to a genuinely impressive 90 miles an hour, and that speed could be maintained in real safety for the entire life of the car using an amount of petrol so small it couldn't be measured. The economies were dazzling, the packaging psychedelic, and the project doomed. The only slightly less eccentric Citroën company had to put a big arm round Panhard's shoulder in 1967. But to those seeing a French car for the first time the really impressive features would be the shape and the colour. I will make no further attempt to describe the shape, but the colour was undoubtedly mauve. A brilliant pale pinkish lavender. A colour that screamed hideously with its grey surroundings. The interior was entirely fashioned from futuristic extruded bakelite the colour of Belgian white chocolate and, moreover, very slightly transparent.

Now I have digressed very considerably already. At an advanced stage in a posting of interminable length, I have still not mentioned organs at all and I am dangerously close to losing you altogether. 'Bicknell can be such an Anorak at times', I hear you say. However, I promise I have not been wasting your time. It has been necessary to set the scene, as only the postings that will follow can demonstrate. My subject has to be drawn from the threads that so markedly distinguish The French Approach to Engineering, for how else am I to describe the bizarre machines that crossed our path at every turn over the next few days?

As if to make this point abundantly clear, fate had ordained that the encounter with the purple motor car would be followed almost immediately by Afternoon Mass at St. Mustache, and the playing of the extraordinary Monsieur Bouillon.

(NOTA BENE This list has visited St. Mustache before; I refer the reader to my posting on this subject dated Wednesday 3rd April 1996 which I will forward to interested readers if they would care to apply by personal email.)

I will attempt to describe our visit to St. Mustache in my next posting.