Pauloni in Paris

This essay first appeared on the electronic

mailing list

![]() Piporg-l

Piporg-l

Part 8

GLORIOUS EXCESS

Before our Tuesday afternoon appointment we had a couple of hours to spare. We left the Church of the Three Persons, having signed our names and written suitable comments in a handsome gold-tooled volume provided for the purpose by the curator of the organ, M. Marcel Ouève, who seemed genuinely disappointed to see us go. On departure, Pauloni decided we should brave the snow and marched down the Boulevard Menilmontant into the Place de la Madeleine. We followed as best we could ('heat was in the very sod', etc.).

My head low, trying to keep the bitter wind out of my face, I walked until I ran into the stationary fur coat in front of the magasin Fauchon. Count Pauloni had stopped in his tracks. Turning to the entrance of the store, he raised a finger towards its door.

'Fauchon!', he cried: 'SUPERBO!'

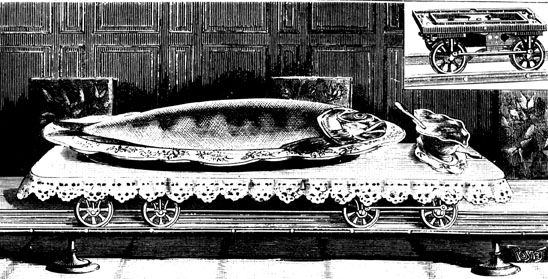

Fauchon is a gourmand's paradise; a food shop from heaven. The main sales floor is stacked from floor to ceiling with comestibles. There is not a single nourishing item amongst them: everything on sale is a completely unnecessary culinary luxury. On one shelf, hand-made jams and preserves of every flavour: blueberry, blackberry, strawberry, raspberry, loganberry, cloudberry, myrtleberry, gooseberry - and violet-, rose- and jasmine-petal. Further along, the fruits themselves, preserved in alcohol. Then every kind of delicious biscuit, from delicate wafer-thin éventails to cinnamon-scented brandy-snaps. Then a whole wall of spices; red, yellow and every other colour; peppercorns of nine different types; saffron worth triple its weight in gold. After that, and yet more precious, a magnificent display of dried truffles, black and white, accompanied by glorious selections of ceps, morelles and other exotic fungi. Counters laden with fresh goods: fish, fowl, beast and perhaps even insect. Mountains of cheese: full-fat Brie dripping over a marble slab; glistening wedges of sheep's-milk Roquefort with its pallid body and curious blue-green veins; the delightful cones and rolls of chèvre, from the goats of the Auvergne.

Fauchon is a gourmand's paradise

And then the chocolates!!!

Our appetite got the better of us. Pauloni marched down to the basement Restaurant and commandeered a large table. The restaurant at Fauchon's is in reality a deluxe cafeteria: you collect a tray and order the dishes you require from a number of stations, each laden with goodies of every description. In fact the array is bewildering: our reaction was simply to stand and gawp. The Count, immediately recognising the awe that strikes lesser mortals when they are presented with an inexhaustible feast, leapt into action: he, at least, seized the opportunity. Directing us to sit down and wait, he proceeded to order those dishes that he thought we would enjoy. The first delivery included fresh bread still warm from the oven, piping hot soups, cold meats garnished with miniature pickles, pates both smooth and coarse, and hard-boiled quails' eggs. We had hardly managed to begin eating these many delicacies before a second delivery brought meat, fish, poultry and game, with huge tureens of piping hot vegetables. The meal continued in like manner. The establishment was, in effect, brought to a grinding halt by Pauloni's attack on its resources (one poor lady-cashier had hysterics). I will not add to your jealousy by describing the rest of the food in detail, except to note (and here I do not exaggerate) that we consumed twelve puddings between the five of us (I exclude my man Cedric, who was, of course, waiting in the street).

On the dot of three o'clock we dragged ourselves away to make the short walk to St. Adolphin, where we met, on the steps, M. Jean-Claude Le Robinet. M. Le Robinet, who is the Official Organ Expert employed by the City of Paris (and may be known to some of my readers as the tonal director of a well-known organ-building company), had kindly arranged the remaining visits in our itinerary.

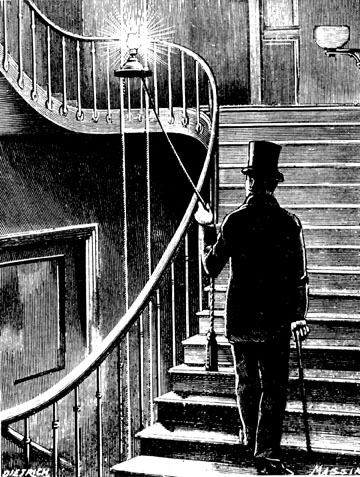

At the foot of the stairs leading to the organ at St. Adolphin he produced an enormous bunch of keys from his satchel and grinned hugely at us. I am delighted to say that M. Le Robinet is an enthusiast. Meeting him I was reminded immediately of what enormous fun the average organ-spotter can have. Here we were, like a bunch of school-children, gloating over the fact that we had the keys to all the best organs in Paris and the afternoon to ourselves!

St. Adolphin! A bizarre church designed by Viollet-le-Duc and Eiffel in collaboration: true gothic in style (if you will excuse the tapered side-aisles and the domed lantern), but made with an iron frame (and falling down because of the rust). On the west gallery, a late three-manual Cavaillé-Coll. It had been through the wars a bit, but we thought it still pretty near authentic, and at least it retained its original mechanism. This was a luxury instrument: two swell-boxes, a Cromorne and a Clarinette, and a proper big Récit in the English manner. But, just like Fauchon's down the street, excess was the key-note. There was a Barker-lever to every manual, and one for the Pedal too. These machines took up a horrifying amount of space, almost causing, through bulk, exactly the dreadful layout of mechanical linkages that they were there, ostensibly, to overcome. Also the entire soft foundation-work of the instrument was rendered inaudible by the astonishing clattering they made. All this in an instrument which, today, one could build with a perfectly ordinary key action, either prompt but slow (tracker) or late but quick (electro-pneumatic).

In a flash, by Metro, to St. Pierre-des-Cailloux! A vast barn of a church, built as a new-town basilica in the 1860s, where they had only ever been able to afford a two-manual, 26-stop, installment of their Cavaillé-Coll. But what a beast, even if incomplete! Divided on either side of the west window, with an unspeakably heavy action, it roared and thundered down the nave like any of its 4-manual brethren. Every stop came straight from a cathedral job, and the 26 stops included independent, full-length Trompettes at 16', 8' and 4' pitch on both Great and Pedal. The effect, together with excellent fonds and a completely unrestrained Plein-Jeu III-V, was quite shattering, but of St. Sulpice quality. In the tutti, even adding the upper octave on the Pedals in a final chord advanced the decibel output another notch. I couldn't help remarking on the contrast between this organ and the countless schemes I have seen emanating from North America in recent years, in which every last dollar has been spent on increasing the number of stop-knobs and gadgets at the console - at the expense of the pipework - and where far larger organs are squeezed into far smaller buildings, solely to satisfy the over-weaning ambition of foolish organists. These silly modern instruments have to be made soft in order to be bearable, and while the resources seem to be there for the performance of music of all kinds, the result is invariably twee and anaemic - at least, up to the point where a handful of unified stops and an egregious horizontal trumpet turn the fortissimo into an incoherent howling ......

And as if to confirm my opinion that one can have too much of a good thing, and that, as far as organ-building is concerned, quality of thinking and manufacture are far more important than numbers of manuals, stops or accessories, we then found, in a hospital chapel, a six-stop one-manual organ by Cavaillé-Coll's successor, Charles Mutin. The six stops were: Montre 8; Salicional 8; Flûte harmonique 8; Prestant 4; Basson 16, and Trompette 8. All were enclosed. Two octaves of pull-down pedals sat below the tiny reversed console. Salicional with the box shut provided a delicate pianissimo. Opening the box it turned into a gallant little geigen diapason. Adding the Montre made the instrument determined and fullsome. The Flûte harmonique made it sound like a big organ (as well as making an excellent fruity sound on its own). The Prestant continued at exactly the same scale and power as the Montre; it was splendidly enlivening while remaining both brilliant and clear. The Trompette pealed with all the ebullience of the French tonal ideal; with the Bassoon added the organ thundered majestically. Shut the box again, and the whole thing all but disappeared. It was unbelievably successful and I could hardly be torn away - although I admit that the absence of the b above middle c, owing to a fault in the action, rendered my mini-recital (of lesser-known preludes by Giovanni Battista Crampi) less than perfect.

Torn away we were, however, to see in a church just by the Père-Lachaise Cemetery; and, in it, M. Le Robinet's latest project.

Over the years the City of Paris has accumulated a considerable stock of redundant organ material. Some dates from the Dufourmantelle-inspired neo-classical rebuilds of the 1950s and 60s. Some is from abandoned projects of the 1970s and 80s. Yet more is of unknown origin, having 'arrived' at the Town Hall at some point in the past. A few years ago Le Robinet decided that he ought to know exactly what the City had collected, and funds were made available to have the pipes removed from storage and laid out for his inspection. It was then of course necessary to assess which of the material was worthy of keeping and which should be scrapped. In order to achieve this Le Robinet persuaded the authorities that he should have each rank of pipes rigged up to a temporary keyboard in some suitable building. A suitable building was found, in the form of a church with no organ, and the project began.

What has now emerged is a complete three-manual instrument, so obviously permanent as to have acquired the skeleton of a new and very grand case. Le Robinet's Dream Organ - for that how it might best be described - rings with the great names of French organ-building. To be sure there are pipes by Cavaillé-Coll, but also many by Mutin, Abbey, Stoltz, Merklin, Mader, Heyer, Convers and others. The soundboards are recycled; the console is by our old friends Bouchon-Derrière (complete with marvellous home-made switch-gear on the Dr. Frankenstein pattern) and the work has been carried out with great devotion by a team of professionals. The Chamades were already in place, though the rest of the Résonance section (made up largely of pedal ranks duplexed to the Positif manual) had yet to be installed. Despite this absence, the instrument made a splendid noise, enough certainly to disturb the inhabitants of Père-Lachaise opposite.

We retired to a nearby café for a cup of hot chocolate, and there we plotted further divisions that could be added to the instrument at a later date. The idea of a Celestial Organ with a Voix Sérénissime appealed particularly to the Organ Expert of the City of Paris. A portable division connected to the console by satellite seemed an obvious tribute to French Technology. I suggested that a mechanical action should be run to the cemetery across the road, where it would operate a batterie of derniers trompettes; en chamade of course, situated underground, in a chamber with solid marble swell-shutters. The key action would be made on the system devised by Dutemps and used by him in the former organ at St. Mustache - thus ensuring that this Last Trumpet would not in fact be playable until the Day of Judgement itself.

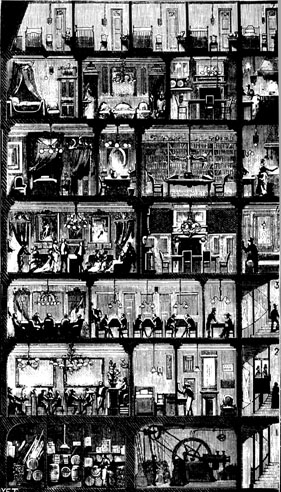

Dinner on the Tuesday night was a splendid affair. We took over the basement of a large traditional restaurant near our hotel. It was old-fashioned: the walls were decorated with obscure mementoes of a long-forgotten Guild of Master-Carpenters. The menus came with no translation, and the shiny-aproned waiter considered it beneath his dignity to explain. The unmistakable smell of Metro tunnels wafted up periodically from the none-too-modern drains. However, the food was incroyable, and the company scintillating. We were graced by the presence of Her Royal Highness the Princess Adelie, who had come to wish us bon voyage. M. Le Robinet entertained us with hilarious accounts of organs he had worked on, clearly treating his entire career as a glorious grand jeu. Count Paulo Pauloni matched every anecdote with tales of concerts given in front of Presidents, Cardinals, Sheiks, and Kings. Young Brad Jaeger had invited a charming friend, a pretty young girl called Fifi who he claimed to have met 'somewhere in Montmartre', and who demonstrated what I took to be traditional French country dancing. Horatio Cordy-Bassett and I tucked into our food (in my case Rognons de Veaux au Sauce des Truffes), greatly appreciating the uproarious atmosphere, and inventing our own sub-text to the events of the last few days.

Dinner on the Tuesday night was a splendid affair

In my bed in the Hotel Récamier afterwards I considered the fact that our expedition to Paris was almost over. It had gone so quickly, and had left us much to see. Yet we had learned so much. I am afraid that much of what I have described seems, to me, merely a confirmation of my own particular bias - especially a tendency to Francophilia that completely discounts any disadvantage to be met in following The French Way. However, I hope it will strike a chord with many, and, for those who have not yet had the good fortune to visit this wonderful country, I hope it will have given an informative glimpse, perhaps even whetting the appetite.

I dreamt that I was standing at the window overlooking the square. Below me all was snowy and quiet. Then, quite suddenly, a large truck appeared. It reversed up to the west end of St. Sulpice. Three tiny figures - surely they were Brad, Horatio and Sister Muriel - heaved open the trailer doors. I peered into the gloomy street to see what was going on. The van driver, a big man wearing a large fur coat, was conferring in the street with someone wearing a bobble hat and an anorak, and carrying a satchel. While they agreed last-minute details and completed paper-work, the van was being loaded. Long shiny organ pipes were disappearing, one after another, into the cavernous interior, followed by sheaves of delicate trackers and assorted mechanical odds and ends. Then, on a stout four-wheeled dolly, the entire five-manual amphitheatre-form console of Cavaillé-Coll's masterpeice. Chalgrin's monumental organ case, folded up, somehow squeezed through the door, and was accommodated in the pantechnicon. Then came Sister Muriel, carrying a silver thurifer, a small crucifix, and an altar-piece by Delacroix. Last was my man Cedric, bringing the lovely gilded chair I had seen in Widor's sitting-room behind the organ. As the lorry drove away I saw a small figure wearing a tiara skating on the ice in the fountain. I rubbed my eyes.

At the Gare du Nord on the journey home the following morning, Brad arrived out of breath (having unaccountably left his passport somewhere), and I was strip-searched by French Customs. This was the first time I have been subjected to this indignity. I couldn't help noticing that Sister Muriel, whose attire was bulging noticably, gave me a broad smirk as she floated through after me. How she disabled the X-ray machine I do not know. In due course I was released, having been deprived of a natty little sample chest-magnet with Ville de Paris written on it. As we prepared, finally, to board the Eurostar for London, a familiar yellow automatic cleaning machine moved up the platform towards us. It bleeped and hummed and flashed at us until we were safely on board. We settled down in our compartment. Pauloni handed his fur coat to the Attendant, who promptly collapsed beneath it.

All good things come to an end!

'At least,' I confided to Horatio as we hurtled towards the Channel Tunnel, 'I will be home in time for tea and the 6 o'clock News'.